The authority of government, even such as I am willing to submit to- for I will cheerfully obey those who know and can do better than I, and in many things even those who neither know nor can do so well- is still an impure one: to be strictly just, it must have the sanction and consent of the governed. It can have no pure right over my person and property but what I concede to it. The progress from an absolute to a limited monarchy, from a limited monarchy to a democracy, is a progress toward a true respect for the individual. Even the Chinese philosopher was wise enough to regard the individual as the basis of the empire. Is a democracy, such as we know it, the last improvement possible in government? Is it not possible to take a step further towards recognizing and organizing the rights of man? There will never be a really free and enlightened State until the State comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power, from which all its own power and authority are derived, and treats him accordingly. I please myself with imagining a State at least which can afford to be just to all men, and to treat the individual with respect as a neighbor; which even would not think it inconsistent with its own repose if a few were to live aloof from it, not meddling with it, nor embraced by it, who fulfilled all the duties of neighbors and fellow-men. A State which bore this kind of fruit, and suffered it to drop off as fast as it ripened, would prepare the way for a still more perfect and glorious State, which also I have imagined, but not yet anywhere seen.

ሰኞ 30 ኖቬምበር 2015

Thoreau's Living Dream !

The authority of government, even such as I am willing to submit to- for I will cheerfully obey those who know and can do better than I, and in many things even those who neither know nor can do so well- is still an impure one: to be strictly just, it must have the sanction and consent of the governed. It can have no pure right over my person and property but what I concede to it. The progress from an absolute to a limited monarchy, from a limited monarchy to a democracy, is a progress toward a true respect for the individual. Even the Chinese philosopher was wise enough to regard the individual as the basis of the empire. Is a democracy, such as we know it, the last improvement possible in government? Is it not possible to take a step further towards recognizing and organizing the rights of man? There will never be a really free and enlightened State until the State comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power, from which all its own power and authority are derived, and treats him accordingly. I please myself with imagining a State at least which can afford to be just to all men, and to treat the individual with respect as a neighbor; which even would not think it inconsistent with its own repose if a few were to live aloof from it, not meddling with it, nor embraced by it, who fulfilled all the duties of neighbors and fellow-men. A State which bore this kind of fruit, and suffered it to drop off as fast as it ripened, would prepare the way for a still more perfect and glorious State, which also I have imagined, but not yet anywhere seen.

Thoreau:- z Civil Disobedient Poet !

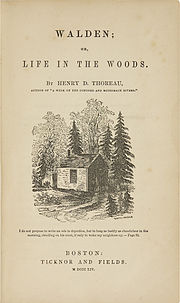

Civil Disobedience and the Walden years, 1845–1849[edit]

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practise resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.

Thoreau needed to concentrate and get himself working more on his writing. In March 1845, Ellery Channing told Thoreau, "Go out upon that, build yourself a hut, & there begin the grand process of devouring yourself alive. I see no other alternative, no other hope for you."[37] Two months later, Thoreau embarked on a two-year experiment in simple living on July 4, 1845, when he moved to a small, self-built house on land owned by Emerson in a second-growth forest around the shores of Walden Pond. The house was in "a pretty pasture and woodlot" of 14 acres (57,000 m2) that Emerson had bought,[38] 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from his family home.[39]

On July 24 or July 25, 1846, Thoreau ran into the local tax collector, Sam Staples, who asked him to pay six years of delinquent poll taxes. Thoreau refused because of his opposition to the Mexican-American War and slavery, and he spent a night in jail because of this refusal. The next day Thoreau was freed when someone, likely his aunt, paid the tax against his wishes.[40] The experience had a strong impact on Thoreau. In January and February 1848, he delivered lectures on "The Rights and Duties of the Individual in relation to Government"[41] explaining his tax resistance at the Concord Lyceum. Bronson Alcott attended the lecture, writing in his journal on January 26:

- Heard Thoreau's lecture before the Lyceum on the relation of the individual to the State– an admirable statement of the rights of the individual to self-government, and an attentive audience. His allusions to the Mexican War, to Mr. Hoar's expulsion from Carolina, his own imprisonment in Concord Jail for refusal to pay his tax, Mr. Hoar's payment of mine when taken to prison for a similar refusal, were all pertinent, well considered, and reasoned. I took great pleasure in this deed of Thoreau's.— Bronson Alcott, Journals (1938)[42]

Thoreau revised the lecture into an essay entitled Resistance to Civil Government (also known as Civil Disobedience). In May 1849 it was published by Elizabeth Peabody in the Aesthetic Papers. Thoreau had taken up a version of Percy Shelley's principle in the political poem The Mask of Anarchy (1819), that Shelley begins with the powerful images of the unjust forms of authority of his time—and then imagines the stirrings of a radically new form of social action.[43]

At Walden Pond, he completed a first draft of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, an elegy to his brother, John, that described their 1839 trip to the White Mountains. Thoreau did not find a publisher for this book and instead printed 1,000 copies at his own expense, though fewer than 300 were sold.[31]:234 Thoreau self-published on the advice of Emerson, using Emerson's own publisher, Munroe, who did little to publicize the book.

In August 1846, Thoreau briefly left Walden to make a trip to Mount Katahdin inMaine, a journey later recorded in "Ktaadn", the first part of The Maine Woods.

Thoreau left Walden Pond on September 6, 1847.[31]:244 At Emerson's request, he immediately moved back into the Emerson house to help Lidian manage the household while her husband was on an extended trip to Europe.[44] Over several years, he worked to pay off his debts and also continuously revised his manuscript for what, in 1854, he would publish as Walden, or Life in the Woods, recounting the two years, two months, and two days he had spent at Walden Pond. The book compresses that time into a single calendar year, using the passage of four seasons to symbolize human development. Part memoir and part spiritual quest,Walden at first won few admirers, but later critics have regarded it as a classic American work that explores natural simplicity, harmony, and beauty as models for just social and cultural conditions.

American poet Robert Frost wrote of Thoreau, "In one book ... he surpasses everything we have had in America."[45]

American author John Updike said of the book: "A century and a half after its publication, Walden has become such a totem of the back-to-nature, preservationist, anti-business, civil-disobedience mindset, and Thoreau so vivid a protester, so perfect a crank and hermit saint, that the book risks being as revered and unread as the Bible."[46]

Thoreau moved out of Emerson's house in July 1848 and stayed at a home on Belknap Street nearby. In 1850, he and his family moved into a home at 255 Main Street; he stayed there until his death.[47]

Later years, 1851–1862[edit]

In 1851, Thoreau became increasingly fascinated with natural history and travel/expedition narratives. He read avidly on botany and often wrote observations on this topic into his journal. He admired William Bartram, and Charles Darwin'sVoyage of the Beagle. He kept detailed observations on Concord's nature lore, recording everything from how the fruit ripened over time to the fluctuating depths of Walden Pond and the days certain birds migrated. The point of this task was to "anticipate" the seasons of nature, in his words.[48][49]

He became a land surveyor and continued to write increasingly detailed natural history observations about the 26 square miles (67 km2) town in his journal, a two-million word document he kept for 24 years. He also kept a series of notebooks, and these observations became the source for Thoreau's late natural history writings, such as Autumnal Tints, The Succession of Trees, and Wild Apples, an essay lamenting the destruction of indigenous and wild apple species.

Until the 1970s, literary critics[who?] dismissed Thoreau's late pursuits as amateur science and philosophy. With the rise of environmental history and ecocriticism, several new readings of this matter began to emerge, showing Thoreau to be both a philosopher and an analyst of ecological patterns in fields and woodlots.[50][51] For instance, his late essay, "The Succession of Forest Trees", shows that he used experimentation and analysis to explain how forests regenerate after fire or human destruction, through dispersal by seed-bearing winds or animals.

He traveled to Quebec once, Cape Cod four times, and Maine three times; these landscapes inspired his "excursion" books, A Yankee in Canada, Cape Cod, and The Maine Woods, in which travel itineraries frame his thoughts about geography, history and philosophy. Other travels took him southwest toPhiladelphia and New York City in 1854, and west across the Great Lakes region in 1861, visiting Niagara Falls, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul andMackinac Island.[52] Although provincial in his physical travels, he was extraordinarily well-read. He obsessively devoured all the first-hand travel accounts available in his day, at a time when the last unmapped regions of the earth were being explored. He read Magellan and James Cook, the arctic explorers Franklin, Mackenzie and Parry, David Livingstone and Richard Francis Burton on Africa, Lewis and Clark; and hundreds of lesser-known works by explorers and literate travelers.[53]Astonishing amounts of global reading fed his endless curiosity about the peoples, cultures, religions and natural history of the world, and left its traces as commentaries in his voluminous journals. He processed everything he read, in the local laboratory of his Concord experience. Among his famous aphorisms is his advice to "live at home like a traveler."[54]

After John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, many prominent voices in the abolitionist movement distanced themselves from Brown, or damned him with faint praise. Thoreau was disgusted by this, and he composed a speech—A Plea for Captain John Brown—which was uncompromising in its defense of Brown and his actions. Thoreau's speech proved persuasive: first the abolitionist movement began to accept Brown as a martyr, and by the time of the American Civil War entire armies of the North were literally singing Brown's praises. As a contemporary biographer of John Brown put it: "If, as Alfred Kazinsuggests, without John Brown there would have been no Civil War, we would add that without the Concord Transcendentalists, John Brown would have had little cultural impact."[55]

Desiderata !

| DesiderataGo placidly amid the noise and haste, and remember what peace there may be in silence. As far as possible without surrender be on good terms with all persons. Speak your truth quietly and clearly; and listen to others, even the dull and ignorant; they too have their story. Avoid loud and aggressive persons, they are vexations to the spirit. If you compare yourself with others, you may become vain and bitter; for always there will be greater and lesser persons than yourself. Enjoy your achievements as well as your plans. Keep interested in your career, however humble; it is a real possession in the changing fortunes of time. Exercise caution in your business affairs; for the world is full of trickery. But let this not blind you to what virtue there is; many persons strive for high ideals; and everywhere life is full of heroism. Be yourself. Especially, do not feign affection. Neither be critical about love; for in the face of all aridity and disenchantment it is as perennial as the grass. Take kindly the counsel of the years, gracefully surrendering the things of youth. Nurture strength of spirit to shield you in sudden misfortune. But do not distress yourself with imaginings. Many fears are born of fatigue and loneliness. Beyond a wholesome discipline, be gentle with yourself. You are a child of the universe, no less than the trees and the stars; you have a right to be here. And whether or not it is clear to you, no doubt the universe is unfolding as it should. Therefore be at peace with God, whatever you conceive Him to be, and whatever your labors and aspirations, in the noisy confusion of life keep peace with your soul. With all its sham, drudgery and broken dreams, it is still a beautiful world. Be careful. Strive to be happy. © Max Ehrmann 1927 |

እሑድ 29 ኖቬምበር 2015

Thoreau's Arguments !

Thoreau asserts that because governments are typically more harmful than helpful, they therefore cannot be justified.Democracy is no cure for this, as majorities simply by virtue of being majorities do not also gain the virtues of wisdom andjustice. The judgment of an individual's conscience is not necessarily inferior to the decisions of a political body or majority, and so "[i]t is not desirable to cultivate a respect for the law, so much as for the right. The only obligation which I have a right to assume is to do at any time what I think right.... Law never made men a whit more just; and, by means of their respect for it, even the well-disposed are daily made the agents of injustice."[5] He adds, "I cannot for an instant recognize as my government [that] which is the slave's government also."[6]

The government, according to Thoreau, is not just a little corrupt or unjust in the course of doing its otherwise-important work, but in fact the government is primarily an agent of corruption and injustice. Because of this, it is "not too soon for honest men to rebel and revolutionize."[7]

Political philosophers have counseled caution about revolution because the upheaval of revolution typically causes a lot of expense and suffering. Thoreau contends that such a cost/benefit analysis is inappropriate when the government is actively facilitating an injustice as extreme as slavery. Such a fundamental immorality justifies any difficulty or expense to bring to an end. "This people must cease to hold slaves, and to make war on Mexico, though it cost them their existence as a people."[8]

Thoreau tells his audience that they cannot blame this problem solely on pro-slavery Southern politicians, but must put the blame on those in, for instance, Massachusetts, "who are more interested in commerce and agriculture than they are in humanity, and are not prepared to do justice to the slave and to Mexico, cost what it may... There are thousands who are in opinion opposed to slavery and to the war, who yet in effect do nothing to put an end to them."[9] (See also: Thoreau'sSlavery in Massachusetts which also advances this argument.)

He exhorts people not to just wait passively for an opportunity to vote for justice, because voting for justice is as ineffective as wishing for justice; what you need to do is to actually be just. This is not to say that you have an obligation to devote your life to fighting for justice, but you do have an obligation not to commit injustice and not to give injustice your practical support.

Paying taxes is one way in which otherwise well-meaning people collaborate in injustice. People who proclaim that the war in Mexico is wrong and that it is wrong to enforce slavery contradict themselves if they fund both things by paying taxes. Thoreau points out that the same people who applaud soldiers for refusing to fight an unjust war are not themselves willing to refuse to fund the government that started the war.

In a constitutional republic like the United States, people often think that the proper response to an unjust law is to try to use the political process to change the law, but to obey and respect the law until it is changed. But if the law is itself clearly unjust, and the lawmaking process is not designed to quickly obliterate such unjust laws, then Thoreau says the law deserves no respect and it should be broken. In the case of the United States, the Constitution itself enshrines the institution of slavery, and therefore falls under this condemnation. Abolitionists, in Thoreau's opinion, should completely withdraw their support of the government and stop paying taxes, even if this means courting imprisonment.

Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also a prison.… where the State places those who are not with her, but against her,– the only house in a slave State in which a free man can abide with honor.… Cast your whole vote, not a strip of paper merely, but your whole influence. A minority is powerless while it conforms to the majority; it is not even a minority then; but it is irresistible when it clogs by its whole weight. If the alternative is to keep all just men in prison, or give up war and slavery, the State will not hesitate which to choose. If a thousand men were not to pay their tax bills this year, that would not be a violent and bloody measure, as it would be to pay them, and enable the State to commit violence and shed innocent blood. This is, in fact, the definition of a peaceable revolution, if any such is possible.[10]

Because the government will retaliate, Thoreau says he prefers living simply because he therefore has less to lose. "I can afford to refuse allegiance to Massachusetts…. It costs me less in every sense to incur the penalty of disobedience to the State than it would to obey. I should feel as if I were worth less in that case."[11]

He was briefly imprisoned for refusing to pay the poll tax, but even in jail felt freer than the people outside. He considered it an interesting experience and came out of it with a new perspective on his relationship to the government and its citizens. (He was released the next day when "someone interfered, and paid that tax.")[12]

Thoreau said he was willing to pay the highway tax, which went to pay for something of benefit to his neighbors, but that he was opposed to taxes that went to support the government itself—even if he could not tell if his particular contribution would eventually be spent on an unjust project or a beneficial one. "I simply wish to refuse allegiance to the State, to withdraw and stand aloof from it effectually."[13]

Because government is man-made, not an element of nature or an act of God, Thoreau hoped that its makers could be reasoned with. As governments go, he felt, the U.S. government, with all its faults, was not the worst and even had some admirable qualities. But he felt we could and should insist on better. "The progress from an absolute to a limited monarchy, from a limited monarchy to a democracy, is a progress toward a true respect for the individual.… Is a democracy, such as we know it, the last improvement possible in government? Is it not possible to take a step further towards recognizing and organizing the rights of man? There will never be a really free and enlightened State until the State comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power, from which all its own power and authority are derived, and treats him accordingly."[14]

An aphorism sometimes attributed to either Thomas Jefferson[15] or Thomas Paine, "That government is best which governs least...", was actually found in Thoreau's Civil Disobedience. Thoreau was paraphrasing the motto of The United States Magazine and Democratic Review: "The best government is that which governs least."[16] Thoreau expanded it significantly:

I heartily accept the motto,—“That government is best which governs least;” and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which I also believe,—“That government is best which governs not at all;” and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have. Government is at best but an expedient; but most governments are usually, and all governments are sometimes, inexpedient.— Thoreau, Civil Disobedience

Non-Cooperation Revolution !

Non-cooperation movement

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2014) |

The non-cooperation movement was significant phase of the Indian independence movement from British rule. It was led by Mahatma Gandhi and was supported by the Indian National Congress. Gandhi started the non-cooperation movement in January 1921 after the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre. It aimed to resist British rule in India through nonviolent means. Protestors would refuse to buy British goods, adopt the use of local handicrafts, picket liquor shops. The ideas of Ahimsaand nonviolence, and Gandhi's ability to rally hundreds of thousands of common citizens towards the cause of Indian independence, were first seen on a large scale in this movement through the summer 1920, they feared that the movement might lead to popular nonviolence.

Contents

[hide]Factors that led to the movement[edit]

Among the significant causes of this movement was resentment to actions considered oppressive such as the Rowlatt Actand Jallianwala Bagh massacre

A meeting of civilians was being held at Jallianwala Bagh near the Golden temple in Amritsar. The people were fired upon by 90 soldiers under the command of Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer. He also ordered the only exit to be blocked. Some 370 protestors were killed and over 1000 others injured. The outcry in Punjab led to thousands of unrests, and more deaths at the hands of the police during protests. The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre became the most infamous event of British rule in India. Gandhi was horrified. He lost all faith in the goodness of the British government and declared that it would be a "sin" to cooperate with the "satanic" government.

Other cause include economic hardships to the common man which the nationalists attributed to the flow of Indian wealth to Britain, ruin of Indian artisans due to British factory-made goods replacing handmade goods, and resentment with the British government over Indian soldiers dying in World War I while fighting as part of the British Army.

The calls of early political leaders like Muhammad Ali Jinnah (who later became communal and hardened his stand), Annie Besant and Bal Gangadhar Tilak (Congress Extremists) for home rule were accompanied only by petitions and major public meetings. They never resulted in disorder or obstruction of government services. Partly due to that, the British did not take them very seriously. The non-cooperation movement aimed to challenge the colonial economic and power structure, and British authorities would be forced to take notice of the demands of the independence movement.

Non-cooperation was recommended by Gandhi to Babu Muhammad Ali and Babu Shaukat Ali for the Khilafat Movement. After the failure of Khilafat Movement, the Congress decided that Non Cooperation was the only way out for India. The movement was undertaken to (a)restore the status of the ruler of Turkey (b) to avenge the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre and other violence in Punjab and (c) to secure Swaraj (independence) for India. Gandhi promised Swaraj in one year if his Non Cooperation Programme was fully implemented. The another reason to start the non-cooperation movement was that Gandhi lost faith in constitutional methods and turned from cooperator of British rule to non-cooperator.

Satyagraha[edit]

Main article: Satyagraha

Gandhi's call was for a nationwide protest against the Rowlatt Act. All offices and factories would be closed. Indians would be encouraged to withdraw from Raj-sponsored schools, police services, the military and the civil service, and lawyers were asked to leave the Raj's courts. Public transportation and English-manufactured goods, especially clothing, was boycotted.

Veterans like Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Bipin Chandra Pal, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Annie Besant and Sammed Akiwate opposed the idea outright. The All India Muslim League also criticized the idea. But the younger generation of Indian nationalists were thrilled, and backed Gandhi. The Congress Party adopted his plans, and he received extensive support from Muslim leaders like Maulana Azad, Mukhtar Ahmed Ansari, Hakim Ajmal Khan, Abbas Tyabji, Maulana Muhammad Ali and Maulana Shaukat Ali.

The eminent Hindi writer, poet, play-wright, journalist and nationalist Rambriksh Benipuri, who spent more than eight years in prison fighting for India's independence, wrote:

When I recall Non-Cooperation era of 1921, the image of a storm confronts my eyes. From the time I became aware, I have witnessed numerous movements, however, I can assert that no other movement upturned the foundations of Indian society to the extent that the Non-Cooperation movement did. From the most humble huts to the high places, from villages to cities, everywhere there was a ferment, a loud echo.[1]

ደንበኛ ይሁኑ ለ፡

ልጥፎች (Atom)