Civil Disobedience and the Walden years, 1845–1849[edit]

Thoreau needed to concentrate and get himself working more on his writing. In March 1845, Ellery Channing told Thoreau, "Go out upon that, build yourself a hut, & there begin the grand process of devouring yourself alive. I see no other alternative, no other hope for you."[37] Two months later, Thoreau embarked on a two-year experiment in simple living on July 4, 1845, when he moved to a small, self-built house on land owned by Emerson in a second-growth forest around the shores of Walden Pond. The house was in "a pretty pasture and woodlot" of 14 acres (57,000 m2) that Emerson had bought,[38] 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from his family home.[39]

On July 24 or July 25, 1846, Thoreau ran into the local tax collector, Sam Staples, who asked him to pay six years of delinquent poll taxes. Thoreau refused because of his opposition to the Mexican-American War and slavery, and he spent a night in jail because of this refusal. The next day Thoreau was freed when someone, likely his aunt, paid the tax against his wishes.[40] The experience had a strong impact on Thoreau. In January and February 1848, he delivered lectures on "The Rights and Duties of the Individual in relation to Government"[41] explaining his tax resistance at the Concord Lyceum. Bronson Alcott attended the lecture, writing in his journal on January 26:

Thoreau revised the lecture into an essay entitled Resistance to Civil Government (also known as Civil Disobedience). In May 1849 it was published by Elizabeth Peabody in the Aesthetic Papers. Thoreau had taken up a version of Percy Shelley's principle in the political poem The Mask of Anarchy (1819), that Shelley begins with the powerful images of the unjust forms of authority of his time—and then imagines the stirrings of a radically new form of social action.[43]

At Walden Pond, he completed a first draft of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, an elegy to his brother, John, that described their 1839 trip to the White Mountains. Thoreau did not find a publisher for this book and instead printed 1,000 copies at his own expense, though fewer than 300 were sold.[31]:234 Thoreau self-published on the advice of Emerson, using Emerson's own publisher, Munroe, who did little to publicize the book.

In August 1846, Thoreau briefly left Walden to make a trip to Mount Katahdin inMaine, a journey later recorded in "Ktaadn", the first part of The Maine Woods.

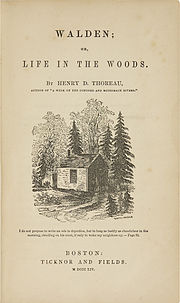

Thoreau left Walden Pond on September 6, 1847.[31]:244 At Emerson's request, he immediately moved back into the Emerson house to help Lidian manage the household while her husband was on an extended trip to Europe.[44] Over several years, he worked to pay off his debts and also continuously revised his manuscript for what, in 1854, he would publish as Walden, or Life in the Woods, recounting the two years, two months, and two days he had spent at Walden Pond. The book compresses that time into a single calendar year, using the passage of four seasons to symbolize human development. Part memoir and part spiritual quest,Walden at first won few admirers, but later critics have regarded it as a classic American work that explores natural simplicity, harmony, and beauty as models for just social and cultural conditions.

American poet Robert Frost wrote of Thoreau, "In one book ... he surpasses everything we have had in America."[45]

American author John Updike said of the book: "A century and a half after its publication, Walden has become such a totem of the back-to-nature, preservationist, anti-business, civil-disobedience mindset, and Thoreau so vivid a protester, so perfect a crank and hermit saint, that the book risks being as revered and unread as the Bible."[46]

Thoreau moved out of Emerson's house in July 1848 and stayed at a home on Belknap Street nearby. In 1850, he and his family moved into a home at 255 Main Street; he stayed there until his death.[47]

Later years, 1851–1862[edit]

In 1851, Thoreau became increasingly fascinated with natural history and travel/expedition narratives. He read avidly on botany and often wrote observations on this topic into his journal. He admired William Bartram, and Charles Darwin'sVoyage of the Beagle. He kept detailed observations on Concord's nature lore, recording everything from how the fruit ripened over time to the fluctuating depths of Walden Pond and the days certain birds migrated. The point of this task was to "anticipate" the seasons of nature, in his words.[48][49]

He became a land surveyor and continued to write increasingly detailed natural history observations about the 26 square miles (67 km2) town in his journal, a two-million word document he kept for 24 years. He also kept a series of notebooks, and these observations became the source for Thoreau's late natural history writings, such as Autumnal Tints, The Succession of Trees, and Wild Apples, an essay lamenting the destruction of indigenous and wild apple species.

Until the 1970s, literary critics[who?] dismissed Thoreau's late pursuits as amateur science and philosophy. With the rise of environmental history and ecocriticism, several new readings of this matter began to emerge, showing Thoreau to be both a philosopher and an analyst of ecological patterns in fields and woodlots.[50][51] For instance, his late essay, "The Succession of Forest Trees", shows that he used experimentation and analysis to explain how forests regenerate after fire or human destruction, through dispersal by seed-bearing winds or animals.

He traveled to Quebec once, Cape Cod four times, and Maine three times; these landscapes inspired his "excursion" books, A Yankee in Canada, Cape Cod, and The Maine Woods, in which travel itineraries frame his thoughts about geography, history and philosophy. Other travels took him southwest toPhiladelphia and New York City in 1854, and west across the Great Lakes region in 1861, visiting Niagara Falls, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul andMackinac Island.[52] Although provincial in his physical travels, he was extraordinarily well-read. He obsessively devoured all the first-hand travel accounts available in his day, at a time when the last unmapped regions of the earth were being explored. He read Magellan and James Cook, the arctic explorers Franklin, Mackenzie and Parry, David Livingstone and Richard Francis Burton on Africa, Lewis and Clark; and hundreds of lesser-known works by explorers and literate travelers.[53]Astonishing amounts of global reading fed his endless curiosity about the peoples, cultures, religions and natural history of the world, and left its traces as commentaries in his voluminous journals. He processed everything he read, in the local laboratory of his Concord experience. Among his famous aphorisms is his advice to "live at home like a traveler."[54]

After John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, many prominent voices in the abolitionist movement distanced themselves from Brown, or damned him with faint praise. Thoreau was disgusted by this, and he composed a speech—A Plea for Captain John Brown—which was uncompromising in its defense of Brown and his actions. Thoreau's speech proved persuasive: first the abolitionist movement began to accept Brown as a martyr, and by the time of the American Civil War entire armies of the North were literally singing Brown's praises. As a contemporary biographer of John Brown put it: "If, as Alfred Kazinsuggests, without John Brown there would have been no Civil War, we would add that without the Concord Transcendentalists, John Brown would have had little cultural impact."[55]

ምንም አስተያየቶች የሉም:

አስተያየት ይለጥፉ